Al-Sabah Al-Yemeni

We were too scared to leave our homes, and most of the shops were shut down or burned,” a resident of Awamiya, in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern province, told me this month. “Anything that moved became a target.” He was referring to the deadly clashes over the past three months between Saudi security forces and residents of this Shiite-majority town.

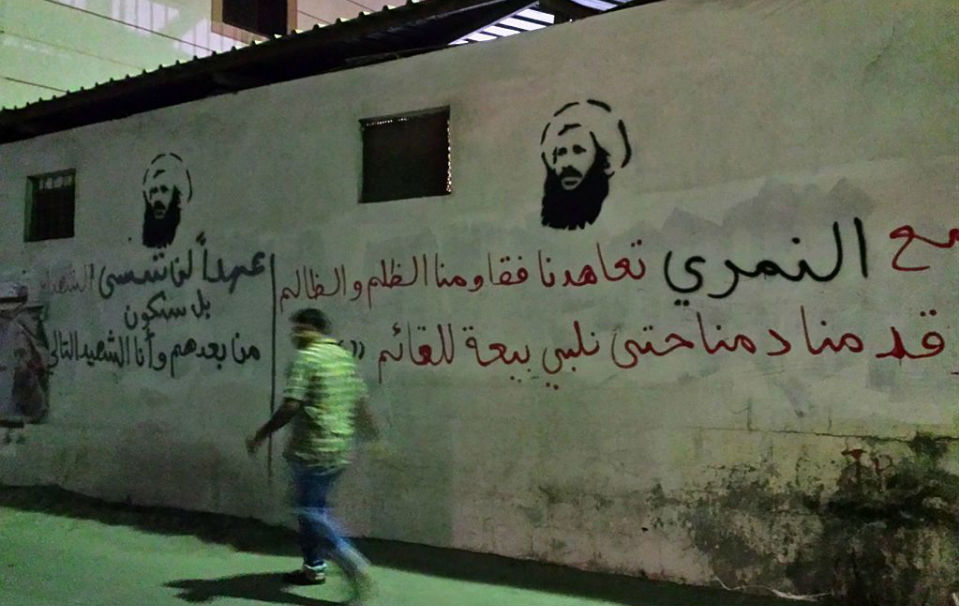

The violence began in May, when security forces began to carry out a planned demolition of Awamiya’s historic Musawara neighborhood, ostensibly to make way for a major development project. They were met with armed resistance from an unknown number of men, many of whom the authorities have sought since 2012 for alleged crimes related to public protests in the area. Government soldiers responded with force — and the violence escalated further after sealing off the entire town on July 26.

Human Rights Watch spoke with five Awamiya residents who did not sympathize with the armed dissenters but faulted government forces for unnecessarily provoking the prolonged fighting. They alleged that Saudi security forces have been arbitrarily shooting at or arresting anyone who emerged from their houses, even in areas far from Musawara, where residents said they saw no precipitating violence.

While the Saudi government has been quick to blame Awamiya’s recent problems on “terrorists,” the roots run much deeper. Saudi human rights activists note that discrimination by the state against the country’s Shiite minority — who make up 10 to 15 percent of the population and mostly live in Eastern province — inflames existing sectarian tensions and produces periodic violent episodes involving demonstrators and security forces.

The hostility and suspicion of the Saudi state, the government-backed Sunni religious establishment, and some elements of the country’s broader Sunni community toward Saudi Shiites reflect more than just long-standing religious intolerance. The contentiousness of regional geopolitics — which Saudi Arabia’s own foreign-policy decisions have contributed to — has also amplified this hostility and suspicion.

In Yemen, for instance, a Saudi-led coalition has launched a war against the Zaydi Shiite armed group known as Ansar Allah, or the Houthis. The coalition has carried out dozens of unlawful airstrikes, with grave consequences for Yemeni civilians.

Even more broadly, the Saudi government’s regional competition with Shiite-majority Iran has fueled its treatment of local Shiites. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have loudly claimed that Iran is expanding its influence in Yemen and other Arab Gulf countries – claims frequently echoed by Washington think tanks funded by these countries.

Saudi officials themselves have propagated rhetoric insinuating links between Saudi Shiites and Iran. In April 2015, Prince Saud bin Nayef Al Saud, the governor of Eastern province, stirred controversy by saying, after assailants shot two policemen in the Shiite-majority town of Qatif, “While our country is going through what it is going through and standing together as one bloc, we find the descendants of the fickle Safavid Abdullah Ibn Saba who try to divide that bloc.”

The Safavid dynasty ruled Iran from the 16th to the 18th century and oversaw the conversion of the country to Shiite Islam. Saudi Shiites say they understood Prince Saud’s comments to mean that he believed Saudi Shiites were a fifth column for Iran.

But while these regional developments have worsened the Saudi state’s suspicion of its Shiite citizens, the persecution of this minority community began long before the current wave of conflict. Human Rights Watch has documented this pervasive discrimination for years: Shiite citizens do not receive equal treatment under the justice system, and the government impairs their ability to practice their religion freely, rarely providing permission for Shiite citizens to build mosques.

Saudi Arabia has historically excluded Shiites from serving in certain public sector jobs and high political office. There are currently no senior Shiite diplomats or high-ranking military officers. Shiite students generally cannot gain admission to military or security academies or find jobs within the security forces. In addition, Saudi Shiites are forced to use an education curriculum that harshly stigmatizes Shiite religious beliefs and practices.

The criminal justice system in particular has been used as a cudgel to mete out draconian punishments against Shiites following egregiously unfair trials. Saudi courts have tried dozens of cases against Shiites for protest-related crimes, even handing down and carrying out death sentences.

Recently, the country’s top court confirmed death sentences for 14 Shiites for protest-related crimes, as well as charges of violence, including targeting police patrols and police stations with guns and gasoline bombs. The court affirmed a lower court ruling convicting nearly all defendants, based almost entirely on confessions they later repudiated in court, alleging that the authorities had tortured them.

These cases follow an old pattern. Human Rights Watch analyzed 10 trial judgments that the Specialized Criminal Court handed down between 2013 and 2016 against Saudi Shiites for protest-related crimes. In nearly all these judgments, defendants retracted their “confessions,” saying they were coerced in circumstances often amounting to torture, including beatings and prolonged solitary confinement.

Regarding the 14 Shiites currently on death row, the court rejected all torture allegations without investigating the claims. It ignored defendants’ requests for video footage from the prison that they said would show them being abused and to summon interrogators as witnesses to describe how the confessions were obtained. The 14 men include Mujtaba al-Sweikat, whom authorities arrested on Aug. 12, 2012 as he was trying to board a plane for the United States to attend Western Michigan University, and Munir al-Adam, who Saudi activists say lost hearing in one ear following beatings by interrogators.

Government-supported Sunni clerics, meanwhile, have drummed up public support for these abusive practices and stoked public ire against Saudi Shiites by persistently targeting them with hate speech. These clerics, some of whom have attracted millions of followers on social media, refer to Shiites using derogatory terms and stigmatize their beliefs and practices. They have also condemned mixing between Sunnis and Shiites, as well as intermarriage between the sects.

In addition, Saudi Arabia’s school curriculum on religion uses veiled language to stigmatize Shiite religious practices as shirk, or polytheism, propounding the idea that such practices are grounds for removal from Islam and will lead its followers to hell.

Such speech has fatal consequences. The Islamic State and al Qaeda have used it to justify targeting Saudi Shiites with violence: Since mid-2015, the Islamic State has carried out attacks against six Shiite mosques and religious buildings in Eastern province and Najran, a southwestern city that also has a large Shiite population, killing more than 40 people. The Islamic State’s news releases mirror government clerics’ language, claiming that the attackers were targeting “edifices of shirk.”

Amid the domestic crackdown and raging wars throughout the region, Saudi Shiites keep trying to explain that their problems are local. In interviews with Human Rights Watch, they told us that what they desire is full integration into the Saudi state as equal citizens.

While the Saudi government may believe that it can clamp down on unrest in Shiite areas by killing “terrorists” and executing protesters after unfair trials, these measures are likely to lead to cycles of protests and crackdowns. Saudi Arabia’s only long-term, durable solution to these problems is to end its repression of its Shiite citizens.

Foreign Policy

خليك معنا